“Who speaks for Nature?” and introducing our new guardian

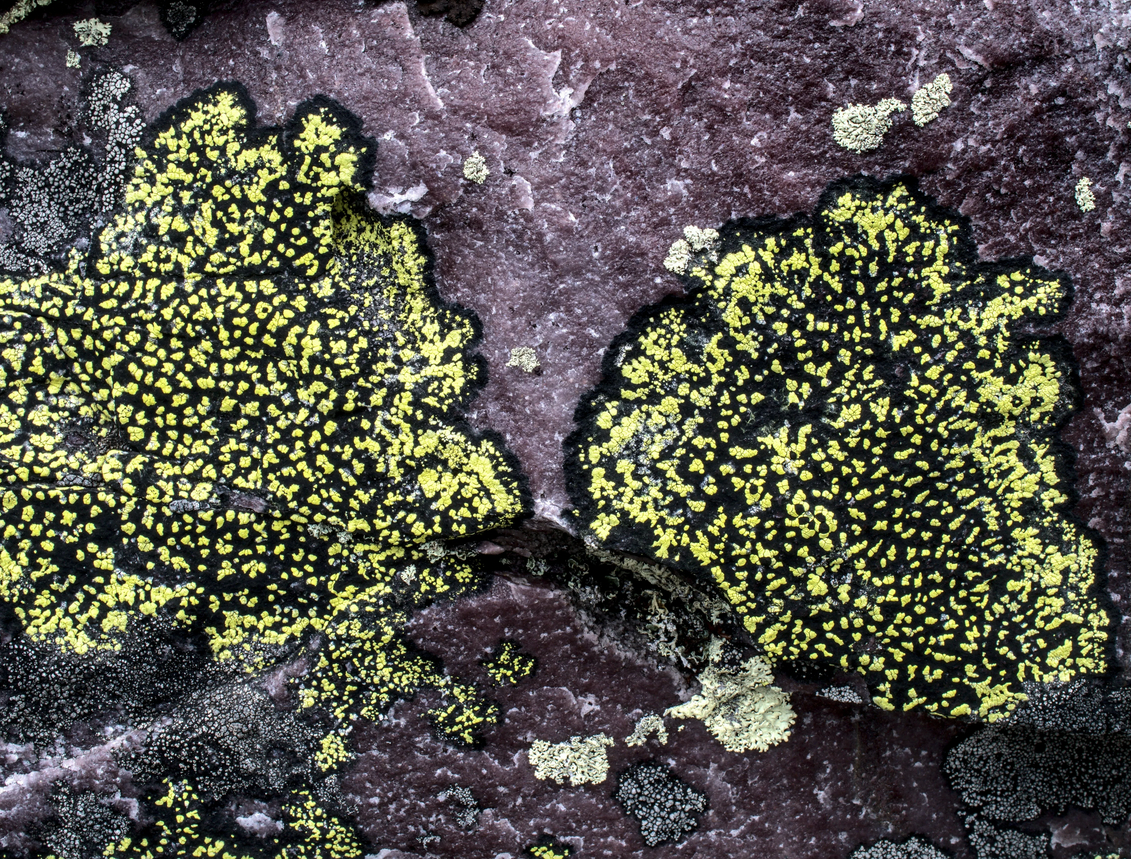

Lichen (We can all be lichen! Explainer below…) Photo by Alexey Melechin on Unsplash

At the heart of the Nature on the Board framework is a guardianship model that allows guardians to speak on behalf of the natural world. This is true for much of the Rights of Nature work, as explained in this brilliant Wellcome Collection article.

The easiest way to understand the guardianship model is to think about a child needing to go to court. Children are not legally able to represent themselves, and so a responsible adult (a guardian) is legally bound to speak on behalf of, and in the interest of, that child. It’s poignant that the same applies for the natural world. Nature is that vulnerable child without a voice and so friends of the natural world must likewise step in and speak not as themselves, but for Nature.

It’s an elegant idea, beautiful in its simplicity. But the obvious problem with it comes from an equally simple question: “Who speaks for Nature?”

To rewind a little, we created Nature on the Board at Faith In Nature in order to bring new, Nature first, perspectives to our decision making process. We realised that every decision we make impacts the natural world, but the one voice missing from the decision making process was Nature’s own.

And, for us, we wanted to go beyond good intentions. We wanted to create something legally rigorous that took great strides towards a workable, practical way of enshrining the Rights of Nature into corporate law. It’s for that reason that we chose, as Nature’s first guardians, the environmental lawyers who, themselves, created the model for us. Nearly 18 months later, Brontie Ansell of Lawyers for Nature remains as one of those guardians and, as a result, we have a robust system with solid legal foundations.

But the whole point was always to bring in a much more varied cast of perspectives. The poet laureate, Simon Armitage, recently wrote that all poets should now be speaking up for Nature. Nature on the Board makes that very literally possible. Likewise it opens the door to the wisdom of indigenous people. The passion of environmentalists. The expertise of zoologists. Even the idealism of children.

So, how do we choose our guardians?

I have written more here on how the guardianship is structured, but to emphasise two points…

Nature’s guardians are independent of the company implementing Nature on the Board. They are not employed by that company to speak in that company’s interests, but contracted as independent experts to speak in the interests of Nature.

Nature’s guardians are not expected to know everything about Nature! In reality, they’re conduits for a much wider pool of perspectives and a channel through which a larger hive-mind of people can speak.

But aren’t we all Nature?

Yes, of course. But that doesn’t mean that everyone is able to shed their human skin and step into a role that requires them to speak on behalf of the more-than-human world. If it did, then all the humans who have ever served on boards (who are also all part of Nature) could be said to have spoken as Nature when it’s plain to see this isn’t the case.

Even though we are all part of Nature, I still want our Nature guardians to be experts in some aspect of the natural world. They should have longstanding experience of working with Nature and a deeper understanding of the natural world than most of us.

The definition of Nature within Faith In Nature’s articles is ‘The natural world and all beings within it’. This definitely includes humans — but humans are not the focus. While we adjust to more ecocentric thinking, we need to do whatever necessary to lose the human bias because this is an intervention that requires us to get out of our own way.

One day, when we can all embody a truer understanding of our place in the natural world, we won’t even need Nature on the Board. Right now, that day seems a long way off.

Don’t we need to start by defining Nature?

Philosophising over what exactly constitutes Nature (separate? non-dual? inner? etc…) inevitably leads to protracted conversations around semantics rather than actual, practical outcomes. And what might feel true one day might change by the next.

Innately, I think we all have enough of an understanding of what Nature is — with enough overlaps between all of our definitions — to get on with the job at hand of protecting the natural world. Personally I’d like to leave the chin stroking for a time when we’re not facing ecological collapse.

As the saying goes: You can keep counting polar bears until there aren’t any left.

Three polar bears. Photo by Hans-Jurgen Mager on Unsplash

Ecological Succession

One thing is for sure, whoever speaks for Nature sets the entire tone of Nature on the Board. If Nature’s guardians are lawyers, Nature on the Board has a very legal skew. But if Nature’s guardians are poets, Nature on the Board becomes more poetic.

The reality is that different companies will likely need a different ‘flavour’ of Nature on the Board depending on how far along they are in the process. And so perhaps the question is not ‘Who speaks for Nature?’ but ‘Who needs to speak for Nature now?’

And, as with all things, Nature has probably already figured this out for us. If Nature on the Board’s role is to rewild the boardroom, then perhaps we first need to look at how Nature rewilds an overgrazed, barren field: Ecological Succession.

By way of explainer from TreesForLife:

When the glaciers retreated from the Highland glens at the end of last Ice Age, how did that barren, glacier-scoured wilderness of rock eventually become rich and varied woodland? The answer is succession, the natural process in which communities of vegetation develop and change over time.

Lichens play a key role in the early stages of succession, accessing minerals in bare rock and helping to begin the process of creating soil. Mosses and grasses can then get established, along with annual and perennial herbs, then shrubs, pioneer woodland, and after centuries, the ‘climax’ vegetation of mature woodland.

If we take this as our guide, before Nature on the Board can even take root, we all need to be the lichen. Primarily, this is cultural and you might not even know you’re doing it — but if you can nudge your organisation towards a more Nature positive perspective, you are creating the conditions for Nature on the Board to be implemented.

The next guardians are those people already in the business in a position to actually implement Nature on the Board. And following them, those able to actually do it.

For that reason, I believe it’s helpful for the first Nature guardians to be Nature lawyers. They’re the people who ensure the system functions and who do so much of the work nobody else notices like establishing the rules, creating legal spaces for the idea to flourish and keeping the board in check so that the whole thing doesn’t unravel.

And that’s really where we’ve focused our efforts until today. But now comes the next phase. We’ve spent many months asking ‘Who needs to speak for Nature now?’ And what feels like a necessary next step is to make this conversation accessible to everyone at Faith In Nature and its surrounding community. And so our newest Nature guardian is somebody who’s done just that for over twenty years: Dr Juliet Rose (no relation!), Head of Development at Eden Project.

Dr Juliet Rose, Head of Development @ Eden Project

Juliet’s background is in Plant Science, Horticulture and Strategic Environmental Management Planning for Degraded Land (so is much better placed to speak about Ecological Succession than me!) and, during her time at Eden has developed a variety of projects including overseas conservation, creative community engagement, community-led planning and regeneration. Her current role at Eden includes the development of Eden outreach programmes, the National Wildflower Centre and Eden international projects.

And on top of all that, she’s just generally brilliant. So, in the spirit of giving Nature a voice, over to Juliet…!

What’s your background?

My academic background is in plant science, horticulture and ecological restoration, but I have also developed community engagement and training programmes. Working with communities and people in the charitable sector has allowed me to meet some really dedicated and determined people who have set their minds to addressing all sorts of issues and challenges.

I’m also fascinated by small islands. I’ve worked on research and conservation programmes on St Helena in the South Atlantic and the Seychelles. You are much more aware of your limits and resources on small islands. They’re also home to extraordinary plants and creatures that you can find nowhere else — when they’re gone, they’re gone. Small islands show us just how fragile the planet is.

More recently, I’ve been working in Latin America on projects in Colombia and Mexico that combine conservation and community development. These megadiverse countries are really important. Collectively, their biodiversity represent a library of resilience. It’s in everyone’s interest that the rainforests, dry forests, grasslands, mountains, deserts and marine ecosystems are invested in, protected and restored.

Closer to home, much of my work is centred around the Eden Project National Wildflower Centre and our Nature Connection programmes. A strong connection with nature is hugely important to our health and well-being, and nature offers an amazing resource for learning and development for all ages.

Can you tell us about some of your work for the National Wildflower Centre?

The National Wildflower Centre is working to reverse the loss of the UK’s wildflower habitats. Over 95% of the UK’s wildflower meadows were lost in the 20th century. They’re important ecosystems for lots of species, but they also bring colour and texture to our landscapes; they are part of our natural heritage, and everyone should have the chance to experience walking (and even skipping!) through a meadow in full bloom. We don’t just restore wildflower habitats in the countryside — we bring wildflowers to urban communities such as Liverpool, Manchester, Morecambe and Dundee so more people can discover them. We are happiest when out as a group of staff and volunteers seed collecting, sowing, planting and harvesting. It feels like we are actively doing something nature-positive.

Poppies in Manchester as part of the National Wildflower Centre’s ‘Tale of Two Cities’ project

There is a science side to what we do, too. The NWC is collaborating on research on plant-pollinator interactions on wildflowers grown on different materials with Exeter University and the genetic integrity of wildflower populations with the Earlham Institute.

We grow seed commercially to support these and other projects, and we launched the Wildflower Bank last year to help landowners create wildflower habitats to achieve Biodiversity Net Gain –an uplift in biodiversity that can be verified, measured and traded, a bit like carbon credits. New legislation in the UK requires new developments to achieve a minimum of 10% Biodiversity Net Gain either onsite as part of a development or offsite via habitat banks that can help to create a nature recovery network across the country.

What are your thoughts on Ecological Succession of the Nature Guardian role? Where do you think we are in the process? (What plant might you be?)

I think this is a great analogy. It reflects the importance of creating and accepting a dynamic and adaptive system — as ecosystems start to develop, species make use of gaps and opportunities, which I think is an important part of the role. Ultimately, each stage supports the next. I think you are at the stage of starting to ‘scrub up’ — structures are in place in the system, and you are starting to diversify and support other species.

Personally, I am a big fan of nitrogen fixers like gorse — I see myself as one of those, adding nutrients that will create the conditions for other species to grow and thrive.

Gorse. Photo by Travis Leery on Unsplash

How do you feel about speaking for Nature?

I’m very happy about it. Humans are a dominant species, and with that comes a responsibility to care for more than just ourselves. Even those who don’t feel that responsibility can’t escape their connection to nature. We can’t breathe, eat, or live without nature — it’s fundamental to our own survival as well as being important in its own right.

From your work in overseas conservation, can you see nature on the board going global?

Absolutely. Corporates are global, and so is their impact. We need this initiative to be replicated at scale and at speed. There is a huge global biodiversity funding gap — hundreds of billions of dollars annually– if we are going to move from a situation of being nature-negative to nature-positive, we need to meet that gap by reducing harm and increasing resources, and we need the leadership roles that can deliver this.

Is there anything else you would like to share?

I am incredibly excited about this opportunity to help Faith In Nature develop this really innovative work, and I hope what we can achieve together will offer inspiration and encouragement for others. Being pioneer like Faith In Nature can be challenging, but it makes it a lot easier for everyone else to follow.